If you are not redirected within 30 seconds, please click here to continue.

Samedi: 10h – 16h HAE

If you are not redirected within 30 seconds, please click here to continue.

If you are not redirected within 30 seconds, please click here to continue.

Then and now: How much more expensive is it to buy a home in 2024 vs. 1994?

With high interest rates, inflation and average home prices exceeding $1 million being sold in cities like Toronto and Vancouver, the dream of owning a home is becoming harder than ever to achieve.

Homes are getting more expensive, but people’s incomes aren’t keeping up. This makes it difficult for many to afford a home. This decline in affordability is largely driven by the existing gap between the number of homes available (supply) and the number of people wanting to buy a home (demand).

RATESDOTCA gathered and analyzed housing data comparing home prices of 1994, a period of peak inflation combined with aggressively high interest rates, and that of 2024 to better understand why it’s so much harder now to buy property.

Here’s what you need to know.

Canada: Then and now

1994:

Median household after-tax income: $32,678 (equivalent to $60,548 in today’s value)

Average house price: $160,064 (equivalent to $296,560 in today’s value)

Mortgage interest rate: 9.53% (5-year conventional mortgage rate)

In the early 1990s, the country went through a recession--a period of temporary economic decline marked by a fall in GDP for two consecutive quarters.

The ‘70s and ‘80s were marked by runaway inflation caused by globalization and an evolving world economy, capped by an oil crisis in the Middle East which upped energy costs internationally.

To combat this inflation, the Bank of Canada began instituting a series of aggressive rate hikes. However, restrictive interest rates caused a shock through the Canadian economy.

Many people lost their jobs during this period. Families who faced financial difficulties during this period disconnected their phone lines, gave up their cars, relied on financial help from charities or borrowed money from family and friends. Those in urban areas also turned to food banks.

Many Canadians during this period struggled to manage mortgage payments, with interest rates hitting up to 9.53% in 1994, leading some to sell their homes.

As they do now in many parts of the country, housing costs consumed most of a family’s household finances.

In 1995, after covering housing expenses, food bank users reported having around $483 per month (around $896 today) for all their other family expenses.

But fast forward to 2024, and it’s all worse now.

2024:

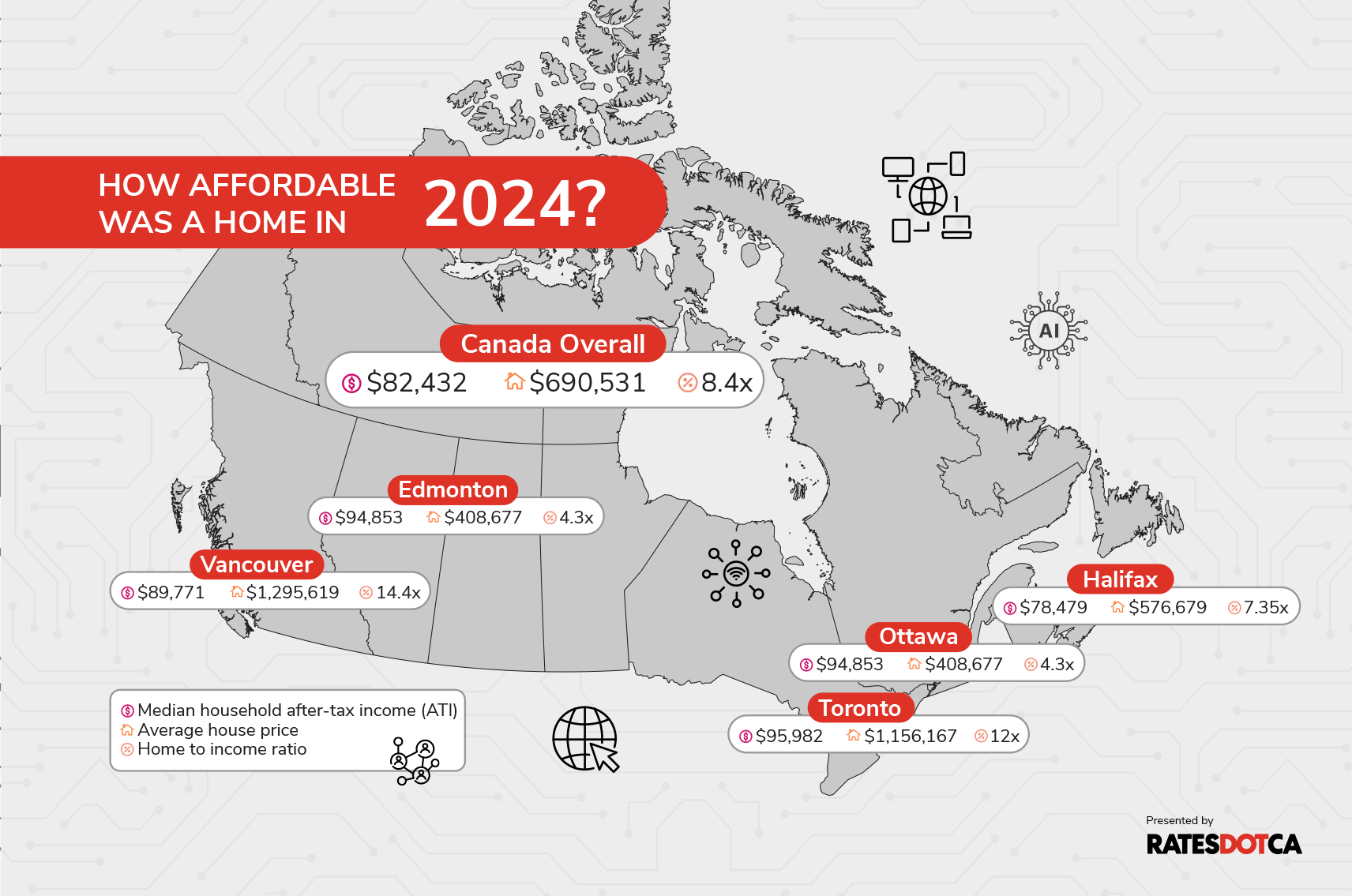

Median household after-tax income: $82,432

Average house price: $690,531 (as of April 2024)

5-year conventional mortgage rate: 6.08% (as of April 2024)

Percentage increase from 1994 to 2024:

Median household after-tax income: 36%

Average house price: 132%

While incomes have risen modestly between 1994 and 2024, home prices have taken off like a rocket.

In 1994, the average home was roughly 4.9 times the average after-tax salary. Now, the home price to income rate is 8.4.

The average home now is 133% more expensive than it was in 1994.

As a result, saving for a down payment, managing mortgage payments and overall cost of living is more challenging.

“It’s just worlds of difference from what it was in the ‘90s,” said Frank Clayton, co-founder and senior researcher at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU)’s Urban Centre for Research and Land Development. “A house could cost a million now, but incomes haven’t changed as much.”

Clayton points out that population growth, the historically low interest rates throughout the pandemic, and not enough properties to meet demand have all led to higher prices. High interest rates in the ‘90s made affording a home extremely difficult – just as they do now, with the policy rate currently sitting at 4.75% (down from 11 months sitting at 5%).

“When interest rates are low, people feel like it’s very inexpensive to borrow money. But when rates are high, like now, it makes it harder for buyers to get into the market,” says Kelly Caldwell, a realtor based in Guelph, Ontario.

However, Canada is a big country, and some markets are better than others. Here’s a snapshot of how each city has fared in their own two-decade long battle over housing affordability.

Toronto

1994:

Median household after-tax income: $39,114 (equivalent to $72,472 in today’s value)

Average house price: $196,731 (equivalent to $364,494 in today’s value)

2024:

Median household after-tax income: $95,982

Average house price: $1,111,944

Percentage increase from 1994 to 2024:

Median household after-tax income: 32%

Average house price: 205%

Canada’s largest city has become a symbol of the country’s housing crisis. Over the past three decades, Toronto’s real estate market has seen unprecedented levels of soaring home prices due to population growth, and high interest rates and inflation.

In 1994, the average home price in Toronto was approximately $196,731 (or $364,494 today). During that time, the median household after-tax income stood at $39,114 ($72,472 today).

Homes were relatively more affordable, costing around 5 times the median household income. This was buoyed by the recession of earlier years and high interest rates, which gave buyers more negotiating power when it comes to home prices.

In 2024, the situation has changed dramatically. The average home price has surged to $1,111,944 , while the median household after-tax income has only risen to $95,982. Now, homes cost about 12 times the median household income, indicating a significant drop in housing affordability.

Toronto, known for its expanding tech and finance sectors, hasn’t been able to keep up with the demand for housing. This has led to a persistent shortage of available units. Despite efforts to increase housing supply, construction rates haven’t matched the city’s population growth. What’s also affecting affordability are the regulatory barriers and building costs, which have made it harder to increase housing supply in the city.

In 2023, Toronto's home builders made a big push towards boosting supply by adding 47,428 new units in the beginning of the year — a 5.1% increase over 2022. However, momentum slowed down due to increasing costs for housing materials and labour, as well as poor sales of new homes.

In many areas, there are more single-detached homes that have been built, but remain unsold, showing that there is less demand for these homes compared to more affordable multi-unit options.

Change in ownership demographics in Toronto

In the 1990s, Toronto's under-50 population saw a decline in homeownership due to weak economic growth, high unemployment, and high interest rates. The average marrying age in Canada rose to 27 for women and 29 for men in 1994, up from 22 and 25 in 1974, contributing to delayed home purchases.

Today’s young adults in Toronto often can't afford homes in their 20s, instead opting to live with parents or rent apartments. The city's household debt to disposable income ratio is among the highest in Canada.

As Clayton notes, "A lot of millennials are still living with mom and dad...and getting partnered up later in life.”

However, millennials still want a single detached home.

“By their mid-30s, these millennials are starting to say 'I don't want an apartment anymore. I don't want to walk down 30 flights of stairs with my kid or my dog all the time. I want a door on the ground. I want a little piece of land. It can just be a little patio or something, but I just want something,” says Clayton.

For many in this age group, home ownership is either beyond their grasp, or only feasible with a large gift from family.

According to a recent StatsCan report, around one in six homes in 2021 owned by people born in the 1990s (17.3%) were co-owned with their parents—a trend that is also common in Vancouver.

Read more: First-Time Home Buyer Incentives in Canada

Vancouver

1994:

Median household after-tax income: $36,254 (equivalent to $67,172 in today’s value)

Average house price: $289,334 (equivalent to $536,067 in today’s value)

2024:

Median household after-tax income: $89,771

Average house price: $1,295,619

Percentage increase from 1994 to 2024:

Median household after-tax income: 34%

Average house price: 142%

During the early 1990s, Canada experienced high levels of immigration, though not as significant as in later decades, according to Canada’s immigration trends and patterns report. Compared to other cities in 1994, Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal were considered top destinations for immigrants.

There was a real estate boom in Vancouver during the 1990s driven by an influx of immigrants, particularly from Hong Kong before the 1997 handover to China, and increased investment from Asian markets.

As a result, Vancouver saw some of the highest residential home prices in Canada during this period.

Now, Vancouver is facing a full-blown crisis in housing affordability. The disparity between incomes and housing prices has widened significantly over the years. In 1994, the average home price was approximately 8 times the average household income, while in 2024, the home price to income ratio has increased to just over 14.

This drastic increase in housing costs relative to income highlights the immense challenges facing potential homebuyers in Vancouver. Factors like zoning and development hurdles, population pressure and supply shortages unique to the city are what’s fueling the housing crisis.

Firstly, according to the CMHC, there is limited land available for new housing projects, particularly in urban areas. What also limits land availability is Vancouver’s geography, bordered by the ocean and mountains. This scarcity drives up prices.

Secondly, the rapid population growth has outpaced the rate at which new housing is being built. Metro Vancouver will top three million residents by July 1, according to a population projection by B.C. Stats. Vancouver is the region’s largest city, with an estimated population of just over 737,000 in 2024, up from 722,000 in 2023.

Halifax

1994:

Median household after-tax income: $33,036 (equivalent to $61,210 in today’s value)

Average house price: $104,513 (equivalent to $364,494 in today’s value)

2024:

Median household after-tax income: $78,479

Average house price: $576,679

Percentage increase from 1994 to 2024:

Median household after-tax income: 28%

Average house price: 58%

The 1990s marked a time when Halifax changed from factories and military to a tech-focused economy. Most residents were employed in the service industry like retail, hospitality, and healthcare, as well in sectors like education, software development, and consulting.

Compared to other major cities, the housing market in Halifax faced fewer pressures from high population growth or significant immigration during this time.

By 1994, homes were relatively more affordable, costing around 3.17 times the median household income.

This is much less true now. Metro Halifax experienced a 3.9% increase in population, adding 19,780 people between 2022 and 2023. As of July 1, 2023, the population in Metro Halifax had reached 518,711.

In 2024, the average home price has surged to $576,679, while the median household after-tax income only increased to $78,479. Now, homes cost about 7.35 times the median household income, indicating a significant drop in housing affordability.

Halifax, and the province of Nova Scotia in general saw a large number from other parts of Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic moving in, causing swift increases in house prices.

However, recent data from Statistics Canada shows that this trend has reversed, with interprovincial migration plateauing for the first time in eight years. As many people moved away from Nova Scotia as moved in from other provinces during the summer of 2023, but that didn’t make the housing market more affordable.

High interest rates have also limited made it more difficult for people to get mortgages, reducing their ability to purchase homes.

Ottawa

1994:

Median household after-tax income: $35,538 (equivalent to $65,847 in today’s value)

Average house price: $146,425 (equivalent to $271,291 in today’s value)

2024:

Median household after-tax income: $94,853

Average house price: $663,503

Percentage increase from 1994 to 2024:

Median household after-tax income: 44%

Average house price: 144%

In the early 1990s, Ottawa had a significantly lower unemployment rate than the rest of Ontario during the recession. But it has continued to outperform the Ontario average since 2001 as more immigrants settled in the city.

Statistics Canada says recent immigrants who settled in Ottawa–Gatineau increased from 3.1% in 2016 to 4.4% in 2021, so with more people choosing to live in the Government City, the demand for housing is bound to increase. Currently, the average home price stands at $663,503. In 1994, the average house price was about 4 times the median household income. By 2024, the house price to income ratio has increased to about 7.

According to the CMHC, in 2023, 63% of new housing starts were for apartments, showing a growing appetite for high-density living. More high-rise apartments are being built in the city center, while fewer single-family homes and row houses are being constructed, and mostly on the outskirts.

They also note that higher construction financing rates and inflation have made it harder to build and raise prices for new homes. Between 2022 and 2023, single-family home starts dropped by 45% and row housing starts by 38%.

Complicated approval processes and zoning rules also caused delays when it comes to preparing land for development, squeezing the already limited supply of housing.

As a result, in Ottawa, there is a high demand for rental housing because of international migration, more students, and fewer people buying homes due to high prices.

Edmonton

1994:

Median household after-tax income: $35,538 (equivalent to $65,847 in today’s value)

Average house price: $114,780 (equivalent to $212,660 in today’s value)

2024:

Median household after-tax income: $94,853

Average house price: $408,677

Percentage increase from 1994 to 2024:

Median household after-tax income: 44%

Average house price: 92%

During the mid-1990s, Edmonton faced tough economic challenges as unemployment rates stayed in the double digits until 1994.

The city was recovering from recession and high interest rates, which led to a population decline between 1991 and 1996 and stagnated metropolitan growth. The livelihood of two Edmonton icons were hanging in the balance: The West Edmonton Mall was plagued by financial difficulties, and the beloved Oilers hockey team was close to relocating to Texas.

But Edmonton’s economy rebounded and became central to Alberta’s energy boom in 2006, which Statistics Canada called “the strongest period of economic growth ever recorded by any province in Canada’s history.”

That’s not to say that Edmonton has had an easy ride through all of this. In 2020, Alberta's economy was hit the hardest of all Canadian provinces due to the COVID-19 pandemic as it dealt with restrictions like physical distancing and a collapse in world oil prices.

Despite those hurdles, in 2024, Edmonton is experiencing a boom – not in oil, but in real estate market, marked by high sales and rising prices. It is expected to heat up even further due to more Canadians choosing to relocate to this more affordable city from places like Toronto and Vancouver.

The city’s residential unit sales have increased nearly 20% since May 2023, according to the Realtors Association of Edmonton, with no signs of slowing, even amidst higher interest rates.

But just how affordable is it?

In 1994, the ratio of home prices to household income was about 3.2, which means you'd have to save up your entire income for over three years to buy the average home. The ratio has inched up to around 4.3 in 2024.

Of course, conventional wisdom says that a healthy ratio is usually around 2.6. Edmonton’s current ratio is higher than this benchmark, which suggests homes are less affordable now compared to the past. But it’s still the lowest among other major cities around the country.

What’s driving Canada’s housing affordability crisis?

With cities around the country currently seeing a higher home price to income than in the ‘90s — arguably a bleaker period in the Canadian economy — it’s worth asking the question: Why are homes so unaffordable now?

Population growth and its impact on housing

According to the latest data from Statistics Canada, the country’s population has surged to just shy of 41 million people in 2024, marking the fastest growth in over six decades. Meanwhile, the housing market has struggled to keep up.

“Immigration has played a big role,” says TMU’s Frank Clayton. “We didn’t have nearly as much immigration back in the ‘90s, which means the demand now is significantly higher.”

Canada has built fewer than 500,000 units of housing, which falls short of meeting the demand. The scarcity of housing supply has led to higher prices and created affordability challenges for prospective homebuyers.

The impact of population growth varies across regions, with Toronto and Vancouver having the worst housing supply shortages.

Clayton says that in the early ‘90s the worst places hit by the recession were also Vancouver and Toronto, but “today, it’s more of a national problem.”

“Interest rates went up in both periods, but this time immigration has played a big role. The last time around, immigration wasn’t nearly as big a force,” he added.

Realtor Kelly Caldwell says there’s a lot of questions about the country’s immigration policies at the federal level. Are they overdoing it by bringing so many people? And how all these people are going to be accommodated with home prices being so high? In some part, immigrants have opted to save on housing costs by living with family.

“It’s not only normal, but it’s desired that you share a home with your elders or other extended family members,” she added. “So that’s also changed things because you’ve got a couple of generations living in the house and able to also get the mortgage for it and pay the bills.”

Finding land sites

While immigration-led population growth has played a role in straining the housing market, it’s not the only factor.

Higher interest rates on mortgages, ballooning construction costs and restrictive municipal zoning have also contributed to the dearth of housing.

Clayton says the length it takes to get land sites ready for development is particularly a problem in Toronto and Vancouver. On the other hand, Ottawa tends to do it faster.

“Ottawa is able to get land onto the market for development faster because it’s only one municipality covering a huge area,” says Clayton. “While in Toronto region, we have Durham, Peel, City of Toronto and all the local municipalities. They are not coordinated at all.”

Looking ahead

For Caldwell and Clayton, the future of housing in Canada looks challenging. Both say that government policies at all levels have not effectively addressed the housing crisis.

“There's a couple of reasons why it's fairly bleak,” says Clayton. The first, he says, is the new climate standard regulations which increase building costs and limit supply.

“As long as you restrict supply and add cost to the supply, there's no way you're going to get affordability turned around very much,” he says.

The second is the type of housing being built.

“Governments are trying to put everybody into an apartment, but lots of people want a single detached house or a townhouse,” he says.

To tackle the lack of housing supply, Caldwell suggests implementing creative solutions such as tax incentives for downsizing, which can particularly encourage older homeowners to move into smaller, more manageable homes, which in turn frees up larger homes for growing families. She also says community land trusts can be used to increase the supply of affordable housing.

"We need to think outside the box and implement measures that can effectively boost the housing supply and make homes more affordable," she says.

Clayton highlights the need for better planning for land use and improved cooperation between different government levels to speed up the development process.

“It's going to be a very gradual turnaround because there's an inherent conflict between the climate initiatives and affordability. We're pushing more and more costs all the time,” says Clayton. “The main factor will have to be housing costs becoming more affordable, but that won't happen overnight.”

While it won’t happen overnight, we can only hope that it doesn’t take another 30 years, either.

Methodology

Home price calculations are based on the monthly average unadjusted home price provided by the Canadian Real Estate Association for January – April 1994, and January – April 2024.

Average median household after tax income calculations are based on Statistics Canada data. Prices are adjusted for inflation.

Get money-saving tips in your inbox.

Stay on top of personal finance tips from our money experts!